It was a joy to be invited by Alan Williams to take part in one of his Values Jam sessions.

The virtual sessions are a conversation between Alan and his guest, based on a value selected by random from a deck of values cards. The value that presented itself from the deck to guide our conversation was gratitude.

We started our conversation reflecting on the meaning of gratitude, and what it might feel, sound and look like. This question immediately drew my mind to the idea of a gratitude practice; simply thinking of three things that we might feel grateful for each day. Research shows that incorporating a gratitude practice into our daily lives can help with reducing depression, stress and anxiety. This is a practice that I myself have drawn real benefit from, in terms of recognising and appreciating the positive aspects of my life, and which without a practice, I may overlook or take for granted.

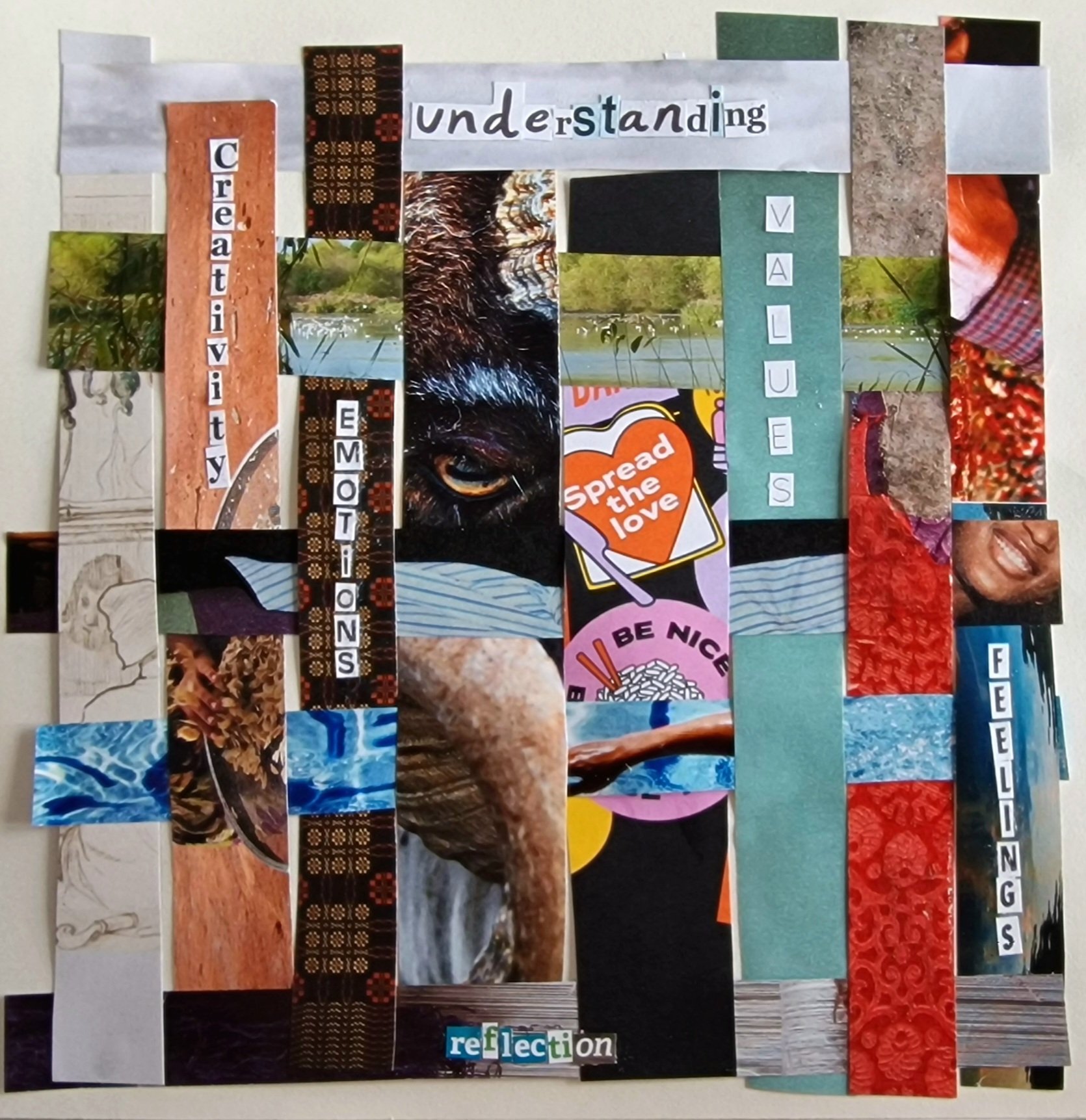

Taking time to acknowledge what it is we feel grateful for reminded me of the first ever facilitation exercise I developed. I was researching for my MA and was interested in speaking to people about their values. I quickly discovered that directly asking people what their most important values were, was mostly met with blank faces, and few words. I needed to use my creativity. So I designed a workshop and started by asking people to write two lists: the first: everything they need to survive, and the second: everything they need to thrive. As with any facilitation approach, I informed my workshop participants that there was no right or wrong answer, and that they only had a couple of minutes to write words that came to mind, so as not to overthink it. After people wrote their lists, we shared them with each other. I have repeated this exercise many times, and it always yields rich conversations and reflections. The survive list helps people connect to what they might be taking for granted, acknowledging what sustains them, such as all that nature provides; whereas the thrive list often illuminates values, relationships or creative aspects that really allow us to live our best lives and versions of ourselves.

The beauty of participating in a facilitated process is that it can create time and space to reflect on and connect to what is important. Of course, there are other ways to slow down and create this time and space for ourselves in our lives, if we do so intentionally. Alan and I both shared that we had taken walks at the weekend, and noticed that the blossom was starting to emerge, and how beautiful it is. As Alan put it, “There is something about slowing down, in order to be able to experience gratitude better.”

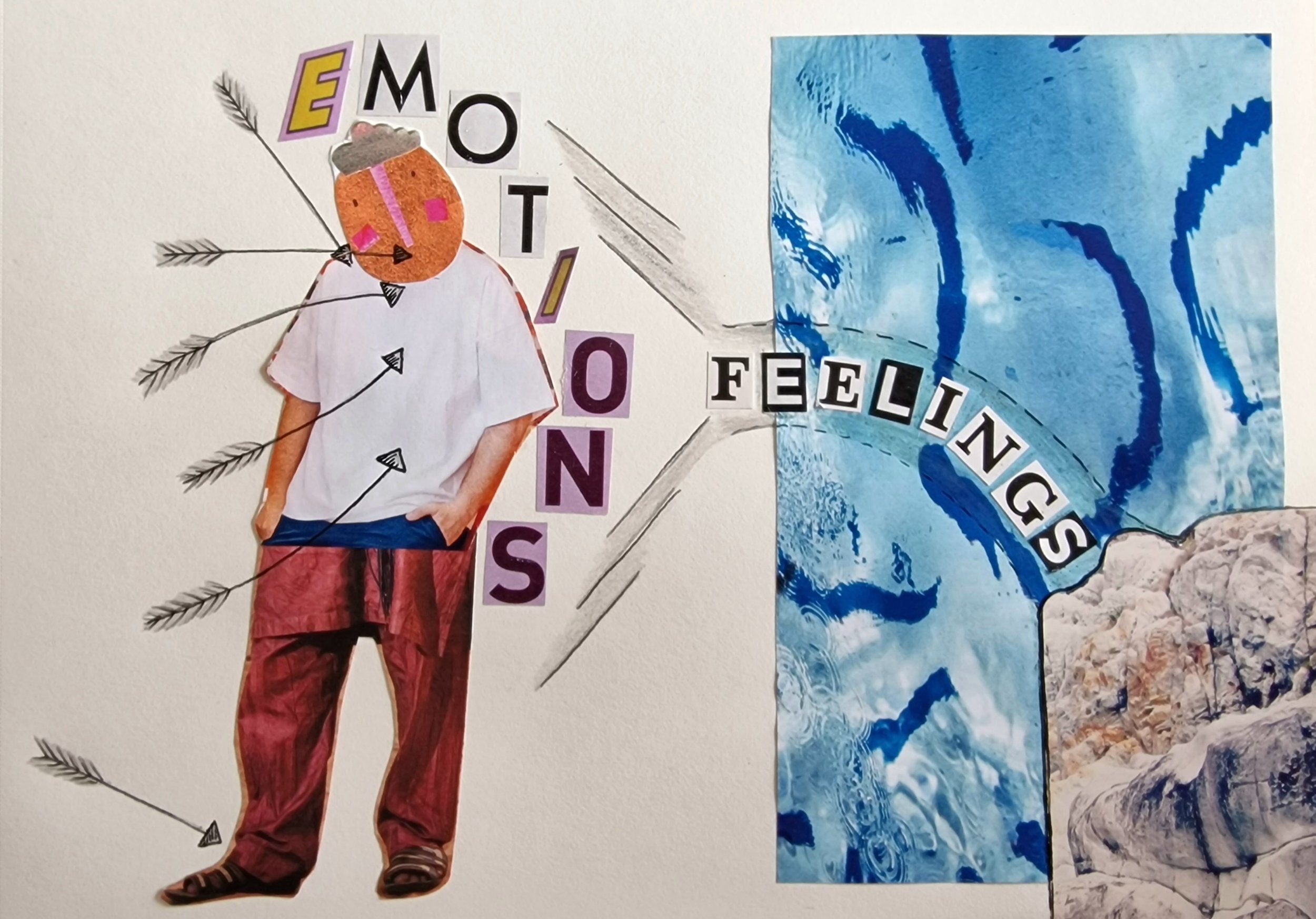

Slowing down is something I firmly believe is needed for us to strengthen our transition to a more regenerative future. Our fast paced, and increasingly distracted lives make it hard to enjoy moments of feeling fully present, embodied and alive to the world around us. For me, there are two important things that influence us and our relationship to slowing down. Firstly, the everyday use of mechanistic language and how it impacts our sense of self. Words like productivity, efficiency, consistency etc can subtly shape our perceptions and expectations of ourselves to have to show up each day the same, as a machine would. Except that we are not machines. As human beings, we are part of nature, and nature exists and evolves in constantly changing cyclical patterns. This leads to the second thing that influences our relationship to slowing down, and that is our relationship to time. Jay Griffiths, in her wonderful book, Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time, reminds us that our common understanding of mono, universal, clock time is in actual fact, a construct of patriarchal, linear and colonial thinking. She introduces us to a myriad of other times that are deeply connected to the natural world and our relationship with it: ocean time, moon time, cow time, bee time. When we begin to bring awareness to our relationship with time and mechanistic language, we can start to understand the impact this might be having on our sense and expectations of self, and what we consider to be a ‘good use of time.’ So the first step into really feeling into the value of gratitude could be to slow down.

Slowing down allows us to bring awareness to the present moment; a tuning in to what is happening both internally in our bodies and minds, and externally in our environments and in others. By slowing down and tuning in, we might also start to recognise what it is we appreciate - in ourselves, others, or the world around us. Just like Alan and myself both felt appreciation for the beautiful blossom on the trees during our walks. In many facilitation approaches we design processes to help meet three basic universal human needs: to be seen, heard and appreciated. The value of appreciation allows us to recognise and acknowledge the reciprocal nature of our relationships with each other and nature. We may want to share that acknowledgement verbally or with an action. For values are not just something to think about, they are to be felt, lived and acted upon.

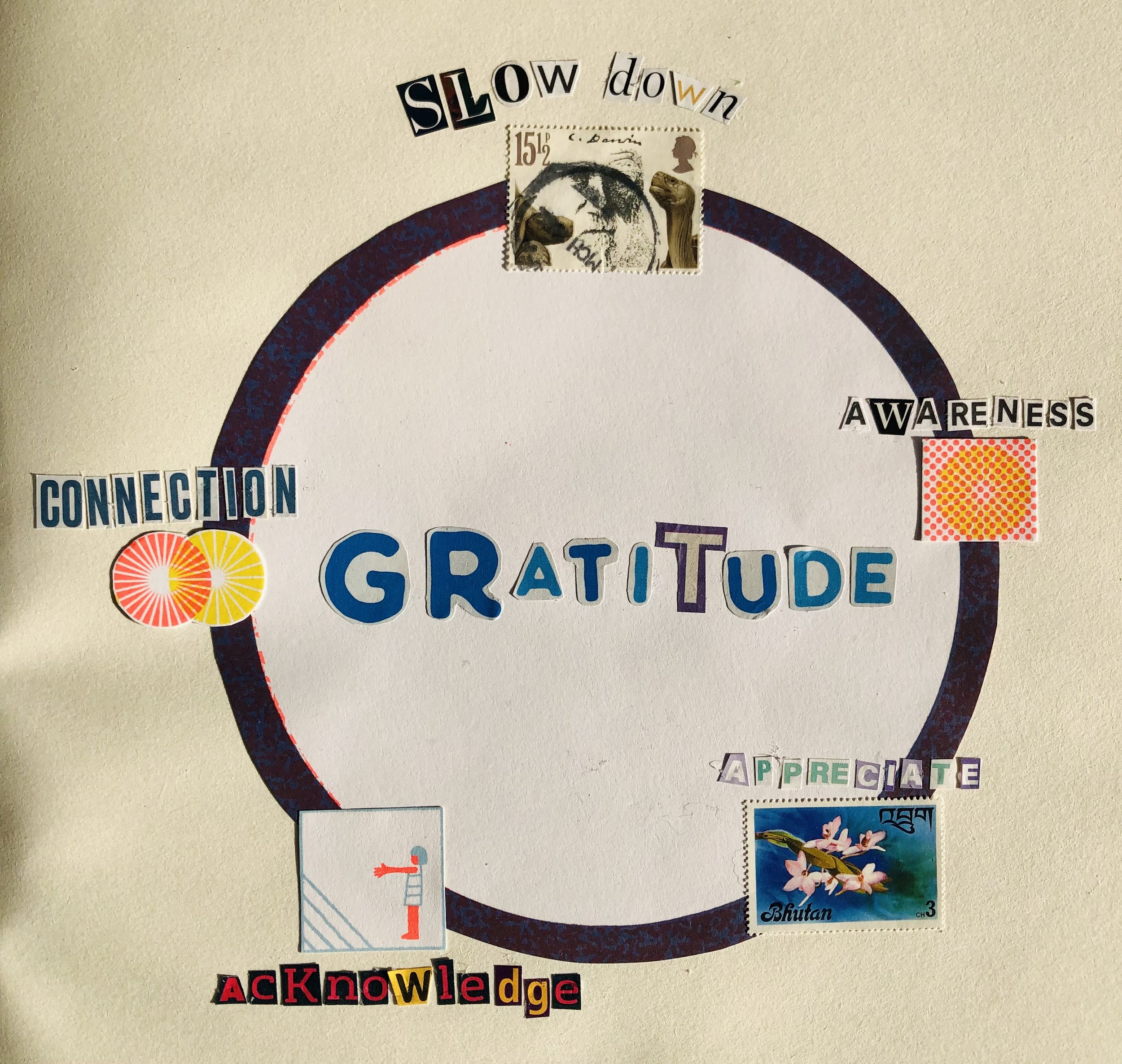

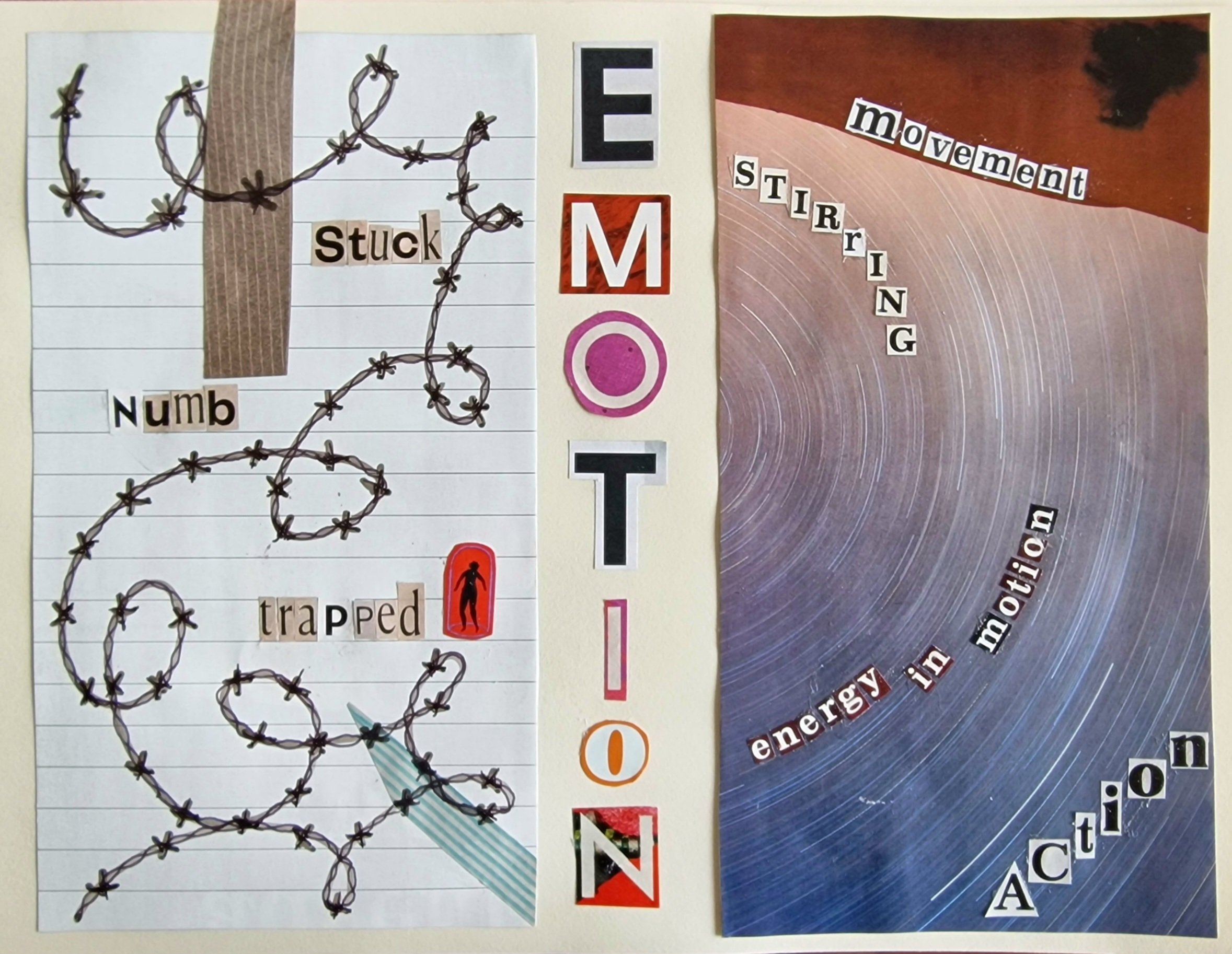

Alan’s final question to me asked what one action was I going to take as a result of our conversation on gratitude. My answer was to relisten to the conversation and take some worm time to digest and process it. Having done that allowed this connective process of values to emerge that I have illustrated in my collage. Our conversation allowed me to further understand that feeling gratitude requires a process of slowing down; appreciating, acknowledging and connecting. Values do not exist in isolation of one another. I am also left with another question from our conversation: how do we sustain values and values-based behaviour? This question has inspired me to return to the series of Values Dialogues that I facilitated for the UK Values Alliance in 2018 and 2019 and look for organisations and communities interested in this powerful process and experience. If you would like to find out more please do get in touch.

Thank you again to Alan for inviting me to take part in this rich conversation, I am very grateful.

The full conversation can be watched here.

Alan is Founder and Managing Director of Service Brand Global, co-author of The 31 Practices and a member of the UK Values Alliance Steering Committee.